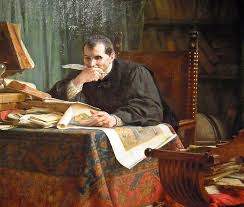

Charm is one of those qualities that is often misinterpreted. For many, it means being warm, polite, or effortlessly likeable. We are taught that charm is about smiling often, speaking kindly, and trying to make others feel comfortable. Yet history shows a different truth. Niccolò Machiavelli, the Renaissance thinker who examined the mechanics of power, believed charm was not about kindness at all. For him, it was about necessity and influence. Charm, in its strongest form, is not about pleasing people but about becoming someone they cannot ignore.

Charm as Necessity, Not Niceness

Being liked may feel pleasant, but it often makes you predictable. Predictability opens the door to exploitation. Likability on its own is fragile. Real charm makes you necessary. It turns you into someone whose presence changes the atmosphere and whose absence cannot be overlooked. People who cultivate this kind of charm bend decisions, secure loyalty, and influence outcomes. Machiavelli wrote, “Men are driven by two principal impulses, either by love or by fear.” The dangerously charming person balances both, drawing others in with attraction while maintaining a strength that commands respect.

Charm as Presence and Restraint

True charm is not about constant attention. It is about restraint. Words are chosen carefully. Approval is rare. Silence carries weight. This type of presence unsettles others just enough to keep them engaged. Instead of feeling too comfortable, people begin to question themselves, adjust their behavior, and seek your recognition. That is where influence begins.

Psychologists have long noted that scarcity creates value. Robert Cialdini, in his book Influence, wrote, “Opportunities seem more valuable to us when their availability is limited.” The same principle applies to attention. When it is given sparingly, people treasure it.

Charm as Architecture

Some may mistake this for manipulation, but it is more deliberate than that. Dangerous charm is like architecture. It is the careful design of interactions that guide people without force. It creates conditions where others reveal themselves freely and where loyalty feels natural, not demanded. As Machiavelli reminded leaders, “It is better to be feared than loved, if you cannot be both.” Dangerous charm blends both qualities into a balance that connects while also commands.

The Three Pillars: Mirror, Void, and Dagger

The Mirror: Reflection replaces flattery. You do not simply tell people what they want to hear. You show them a part of themselves they fear but also hope could be true. Saying to someone, “Your silence is often mistaken for weakness, but it is also why you hold more power than you realize,” reframes an insecurity as strength. That sense of recognition creates attachment.

The Void: Strategic absence is one of the most powerful tools of charm. By giving full attention in one moment and withdrawing in another, you create cycles of desire. Others wonder if they have lost your interest and invest more energy into keeping it. Research confirms that uncertainty intensifies attachment. Used wisely, silence and absence magnify your presence.

The Dagger: This is sharp truth delivered with care. It is not cruelty but clarity. A statement like, “You are not afraid of failure, you are afraid of being ordinary,” strikes deeply. Such words linger because they reveal hidden fears. The person feels compelled to respond, often by proving you wrong on your terms.

Strategic Silence and Mystery

History’s strongest figures understood the power of silence. Napoleon Bonaparte often let others speak first, and when he did speak, his words carried authority. The same is true in relationships. A rare, well-placed gesture outweighs countless routine ones. In the digital age, where many compete for attention every moment, the one who chooses moments carefully holds more influence. Scarcity increases value everywhere.

The Discipline of Dangerous Charm

Becoming dangerously charming is not a trick but a discipline. It requires control over emotions and the ability to turn pain or betrayal into strength. Psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, who survived the Holocaust, wrote, “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.” Those who practice dangerous charm live this lesson. Every wound becomes a source of wisdom. Every failure becomes a lesson in strategy.

Criticism is not met with anxious defense but with calm inversion. If called manipulative, one might reply, “Perhaps you are finally noticing how influence works.” If called arrogant, one could say, “Confidence feels threatening to those who doubt themselves.” In this way, criticism reveals more about the other person’s insecurity than about your flaws.

Freedom as the Highest Form of Charm

The peak of dangerous charm is freedom. The one who no longer needs approval cannot be controlled. Their independence makes them both desired and feared. Epictetus, the Stoic philosopher, said, “No man is free who is not master of himself.” Dangerous charm arises from this mastery. The free individual does not chase validation. Others pursue them precisely because they cannot be bound.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Dangerous Charm

Charm based only on kindness is fragile. Charm built on necessity endures. Machiavelli’s insight reveals that true charm is not about being liked but about becoming essential. Practicing this kind of charm means approaching interactions with discipline, using silence and scarcity wisely, and speaking truths that cut through illusion.

The dangerously charming do not beg for loyalty; they make betrayal unthinkable. They do not seek constant attention; they make absence powerful. In a world where many strive only to be liked, they stand apart by being unforgettable. Machiavelli taught, “The ends justify the means.” In the realm of charm, the end is influence, and the means are restraint, clarity, and freedom.